Thirteen weeks into the “Revolutionary FAR Overhaul” (RFO) process [EO 14275], a total of eight parts out of the 50 prescriptive parts of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) have been rewritten and issued as model deviations. Halfway through the 180-day deadline of October 12, 2025, model deviation texts for FAR Parts 1, 34, 10, 43, 18, 39, 11, and 6 have been released, leaving 42 parts, or 82%, for the remaining 88 days.

The accelerated timeline to streamline a 2,000+ page regulation that has been written and amended countless times over four decades will undoubtedly create a product that will require refinement and discussion. This insight is the first in a series to examine the critical provisions of the current and soon-to-be “legacy” Subpart 9.4 of the FAR.

RFO Process

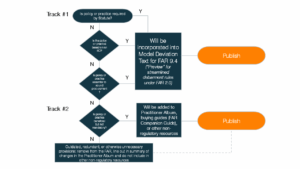

The 2-phase RFO process begins with issuance of FAR deviations and non-mandatory guidance within the first 180 days (October 12, 2025) and ends upon completion of formal rulemaking (no specified deadline). OMB Memorandum M-25-26, Overhauling the Federal Acquisition Regulation (May 2, 2025). Phase I follows a two-track process.

In Track 1, the FAR Council issues model deviation text for each FAR part which agencies must adopt through class deviations. Model deviation texts shall retain only provisions required by statutes, executive orders, or essential to sound procurement. Track 2 strips unnecessary provisions and processes from the FAR, retaining and moving beneficial but non-mandatory content to a “FAR Companion Guide” containing non-regulatory language. Together, the streamlined FAR and the non-regulatory FAR Companion Guide make up the “Strategic Acquisition Guidance” (SAG).

After the FAR Council has posted model deviation guidance for all FAR parts, Phase II will begin with formal notice-and-comment rulemaking per 41 U.S.C. 1707. Rulemaking will be based on the model deviation text for each FAR part, public comments, and agency operational experience and input on deviation language and buying guides. All FAR requirements not mandated by statute included in FAR 2.0 will sunset after four years unless renewed by the FAR Council. The FAR Council included a “caveat” in its FAR Deviation Guide indicating that statutory changes and recissions of current EO requirements to further align with the Administration’s policies will also be in the works.

Dramatic shifts announced by the new administration in its enforcement policies (e.g., here, here, and here) have created a high degree of uncertainty in the government contracting community and, among suspension and debarment (S&D) practitioners, a heightened anticipation for the streamlined debarment rules in FAR Subpart 9.4.

This series of in-depth insights examines whether each key feature, principle or process that is a part of the current debarment system has a basis in statute or executive order and, if not, should the provision be retained in the streamlined FAR rule as essential to sound procurement. We begin with those provisions most firmly rooted in statutes including:

- The suspension and debarment remedies;

- The authority and discretion of federal agencies to exclude contractors;

- Enumeration of certain causes for suspension or debarment;

- The government’s discretion to exclude contractors for unspecified offenses, misconduct, or poor performance;

- Compelling reasons exceptions and waivers; and

- Government-wide effect of an exclusion.

Statutory Origins of the Debarment Remedy

Contractor responsibility emerged as a statutory requirement in the late 19th century when Congress enacted the precursor to the False Claims Act in 1863. Act of March 2, 1863, 12 Stat. 696 (1863). The precept that only responsible contractors may receive contract awards was explicitly articulated by the 48th Congress in 1884, requiring “award [of contracts] in every case shall be made to the lowest responsible bidder…” Act of July 5, 1884, Ch. 217, 23 Stat. 109 (1884). Nearly a century and a half ago, Congress created the authority to exclude non-responsible bidders from receiving government contracts and vested the discretion to make that determination with the Executive branch.

From that early foundation creating the basis for exclusion, nearly a century of federal laws expressly authorizing debarment for a variety of offenses and violations ensued. Statutes expressly authorizing or requiring debarment for certain offenses or violations include:

- Buy American Act of 1933 (41 U.S.C. §§ 8301-8303) for unauthorized use of non-American produced materials in government contracts including intentionally affixing “Made in America” labels to products not made in the U.S.;

- Davis-Bacon Act of 1931 (40 U.S.C. §§ 3141-3148) for failure to pay prevailing wages on public works projects;

- Walsh-Healey Public Contracts Act of 1936 (41 U.S.C. §§ 6501-6508) for labor violations in government contracts;

- Contract Work Hours and Safety Standards Act of 1962 (40 U.S.C. § 327) for failure to pay workers prevailing wages;

- Service Contract Act of 1965 (41 U.S.C. §§ 351-358) for labor violations in service contracts;

- Clean Air Act of 1970 (42 U.S.C. § 7606) for criminal convictions of the Clean Air Act;

- Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1972 (33 U.S.C. § 1368) for criminal violations of the Clean Air Act;

- Drug-Free Workplace Act of 1988 (41 U.S.C. § 8102(b)) for “unlawful manufacture, distribution, dispensation, possession, or use of a controlled substance” in the federal contractor workplace;

- Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2012 (Pub. L. 112-74) (and all subsequent appropriations legislations including continuing resolutions) requires consideration of debarment for federal felony convictions and tax delinquencies; and

- Protecting Business Opportunities for Veterans Act of 2019 (38 U.S.C. § 8127(k)) for violations of subcontracting limitations by veteran-owned small businesses.

Codifying the Debarment Remedy

Since the 1940s, Congress began passing laws codifying, clarifying and reinforcing the government’s authority to impose discretionary suspensions and debarments.

The Armed Services Procurement Act (ASPA) of 1947 (Pub. L. 80-413) contained the responsible bidder requirement, forming the statutory basis for suspension and debarment provisions in the Armed Services Procurement Regulation (ASPR).

The Federal Property and Administration Services Act (FPASA) of 1949 (Pub. L. 81-152) similarly incorporated the responsible bidder requirement and provided the statutory basis for suspension and debarment in the Federal Procurement Regulations (FPR) applicable to the newly established General Services Administration and other civilian agencies.

The “responsible bidder” requirement codified in the ASPA and FPASA, combined with the proliferation of statutes authorizing debarment for specific legal violations, provided the statutory foundation for comprehensive debarment provisions and procedures in federal procurement regulations.

With the issuance of the ASPR (1948) and the FPR (1959), the framework for a new debarment regime was established. The earliest iterations of the debarment rules included causes for exclusion (including conviction/judgment for contract-related offenses, antitrust violations, clear and convincing evidence of serious contractual violations, and debarment by another agency), duration of debarment, and notice – to include the cause and duration – for the action taken.

Absent from the early procedures in the ASPR and FPR were basic procedural safeguards such as pre-debarment notice, the opportunity to contest an action and fact-finding hearings. Other features of the current debarment regulations such as the compelling reasons exception, government-wide effect, and reciprocity would take several years and, in some cases, decades to emerge.

Indeed, by the mid-1970s, a proliferation of procedural approaches to debarment emerged among civilian agencies and the Defense agencies and military components, creating confusion, inconsistency and inefficiency. In the 1980s, Congress began to impose uniform rules within defense procurement and required reciprocity between defense components and civilian agencies.

In 1981, Congress included a number of debarment provisions as part of the Department of Defense Authorization Act of 1982 (Pub. L. 97-86). Among other key provisions, it required military departments to recognize and apply exclusions imposed by other agencies.

The statute also explicitly recognized the “compelling reason” exception to allow award to excluded contractors. This key feature gave the military components the necessary flexibility to support critical programs by granting them the ability, on a case-by-case basis, to waive an exclusion despite its government-wide effect.

Importantly, the law set the scope of agency discretion broadly by defining the key terms:

“‘Debar’ means to exclude, pursuant to established administrative procedures, from Government contracting and subcontracting for a specified period of time commensurate with the seriousness of the failure or offense or the inadequacy of performance.

‘Suspend’ means to disqualify, pursuant to established administrative procedures, from Government contracting and subcontracting for a temporary period of time because a concern or individual is suspected of engaging in criminal, fraudulent, or seriously improper conduct (10 U.S. 2393(c)(1) and (2)).”

Matters that may be subject to suspension and debarment include “failure[s],” “inadequacy of performance,” and “seriously improper conduct” by the contractor, well beyond the causes for debarment authorized within existing statutes. Moreover, implicit within the definitions are agencies’ inherent discretion to determine what contractor failures, poor performance or misconduct warrant exclusion to safeguard the integrity of federal programs.

By statute, federal agencies are authorized to exercise discretion to exclude contractors for a wide range of causes including specified and unspecified offenses, serious misconduct, and poor performance. Furthermore, all agency exclusions are given government-wide effect and, on a case-by-case basis, may be waivable through a “compelling reason” exception. Thus, the substantive and procedural cornerstones for FAR Subpart 9.4 were laid in 1981.

Later in this FAR insight series, the Government Contracts Practice will examine the foundation in statutes and executive orders of the following key aspects of debarment:

- Reciprocity between FAR and NCR exclusions

- Necessity for independent suspension and debarment officials

- Definitive debarment period

- Lead agency coordination and designation

- The Interagency Suspension and Debarment Committee (“ISDC”)

- Minimum due process protections for Respondents including:

- Notice

- Opportunity to contest the action via oral or written submissions

- Fact-finding hearings

- Written determinations

- Administrative agreements to settle S&D actions

- Fact-finding

- Affiliation and imputation principles

- Consideration of aggravating and mitigating factors

- The concept of “present responsibility”

Stay tuned as the practice dives deeper into the statutory underpinnings of these critical debarment processes and safeguards.